I don’t spend a lot of time going over data or analyzing numbers—that’s why I read people like

, and .But I have been diving into this new report from Catalist, “WHAT HAPPENED IN 2024,” which does what it says on the label. We need to understand who voted and who didn’t, and Nate Silver quotes Catalist in his own confidently emphatic headline,

Turnout didn’t cost Kamala Harris the election

No single demographic characteristic explains all the dynamics of the election; rather we find that the election is best explained as a combination of related factors. Importantly, an overarching connection among these groups is that they are less likely to have cast ballots in previous elections and are generally less engaged in the political process.

Remember that last bit (there will be a quiz): “they are less likely to have cast ballots in previous elections and are generally less engaged in the political process”

Back to

—he writes,In past elections, however, new voters were also Democratic, enough to more or less cancel this out. This time, however, the majority of new voters picked Trump.

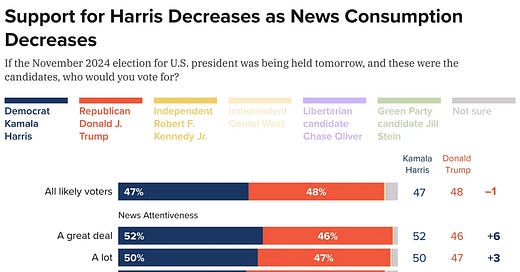

Put another way, Democrats performed poorly among marginal voters in general: people who don’t read the news that much, and whose political views don’t match the ideologically “consistent” views of strong partisans. Young voters, voters of color, and voters without college degrees are overrepresented in this cohort, all groups that Democrats struggled with in 2024 compared to previous elections.

Remember this too: Democrats performed poorly among marginal voters in general: people who don’t read the news that much, and whose political views don’t match the ideologically “consistent” views of strong partisans.

Nate Silver sums it up nicely:

Democrats lost a net of 6.4 million votes from repeat voters switching, mostly to Trump (5.5 million) but some to third parties (0.9 million).

Then they lost a net of 2.7 million votes due to dropoff voters.7

Further, they lost a net of 0.8 million votes because more new voters went for Trump.

As I’ve previously mentioned relentlessly repeated, first-time voters broke for Trump, 54%-45%. That was a huge reversal from four years ago, when new voters strongly favored Biden, 64%-32%.

Now, data analysis by Catalist shows:

The number of new voters returned to 26 million people, lower than the high water mark of 2020. Importantly, these new voters fell below 50% support for the Democratic candidate for the first time in our dataset.

For the first time in our dataset!!! Significant, yes?

After years of historically high support among Democrats, a significant share of young voters swung toward Republicans. Voters under the age of 30 dropped from 61% Democratic support in 2020 to 55% in 2024. Similar support drops are evident when examining voters by generational cohorts, such as Gen Z or Millennials. These drops were larger than drops for any other generation or age group, and other trends in the demographic data, such as drops among different racial groups and the gender gap, were more pronounced among young voters than the rest of the electorate.

Here come more italics: Voters under the age of 30 dropped from 61% Democratic support in 2020 to 55% in 2024. Similar support drops are evident when examining voters by generational cohorts, such as Gen Z or Millennials.

Now, as

writes, Democrats and the donors and strategists who want to influence them are considering projects like looking to “find the next Joe Rogan.” He’s not enthusiastic about that idea:As many on social media pointed out, the idea of rich donors trying to buy online relevance makes the party look desperate, inauthentic, and ridiculous. Democrats learned nothing from our most recent asskicking, which is why this story was so disappointing and enraging to so many.

Pfeiffer also quotes Catalist:

Democrats continue to do very well with hyper-engaged “Super Voters,” but struggle with people who engage with politics less frequently. This matters in communications because political engagement tends to correlate with news consumption. More frequent voters are more likely to follow the news, mostly from traditional sources. The voters we are losing are much harder to reach. They almost never engage with traditional media. They don’t watch cable news or read the New York Times or Wall Street Journal. Since trust in the media is at an all-time low (and sinking!), even if these less engaged voters stumble onto political coverage, they are unlikely to find it credible.

One more use of that good ol’ italic font: More frequent voters are more likely to follow the news, mostly from traditional sources.

Let’s recap:

The 2024 election was determined by turnout among people who don’t usually vote, don’t keep up with the news, and don’t think politics has much to do with their lives. Young people were particularly disengaged in this election.

In my spectacularly poorly timed open letter to David Hogg, published a few hours before the story broke about the pushback to his PAC’s plan for supporting challengers to some older incumbent Democrats, I wrote:

It’s the 42 percent solution—if you’re trying to “solve” how to keep political power in the hands of billionaires, special interests and oligarchs.

42 percent of young people ages 18-29 turned out to vote in 2024, according to data from the non-partisan research center CIRCLE, down from 50% in 2020.

But voters aged 50 or older were 52 percent of the electorate.

They’re the ones electing officials who won’t vote for gun safety, health care, voting rights, the environment, gender equality and racial justice, and all the other issues that younger voters care about.

Dan Pfeiffer and others are, of course, right to say that Democrats need to reach young people where they are—meaning YouTube over CNN, content creators over network producers. Sure, absolutely.

But there’s a risk that political content, ads and other forms of communication to influence voter turnout falls on ears as deaf as mine are, whenever someone wants to talk to me about sports—either in person or through the media.

I feel the same way about cars.

How many people who will be listening to “the next Joe Rogan” will be paying close attention to the bits about candidates, and how many will be more focused on the “sports and lifestyle” content they tuned in for, or fanboy conversations about video games?

The headline in that Times story is on the, er, money—Democrats Throw Money at a Problem—and

is right to write, “It read as if a bunch of rich Democrats were trying to buy magic beans to grow a Liberal Joe Rogan.”I agree with Dan Pfeiffer that new media networks and content that young people might actually want is vital, but I want to go back to those “Super Voters” he was writing about. Lately, they haven’t been super good at turning out.

Shouldn’t we be paying more attention to those people who wouldn’t rather spend their time playing video games than watching/reading/posting/sharing (reputable) news? Aren’t they the low-hanging fruit every political campaign wants to harvest first?

Let’s not give up on reaching people who start with a base of caring about politics, and can be motivated by more than grievance, and a desire to “own the libs.”

The door to traditional media may be closing, but it’s still the one that’s working.

Dan Pfeiffer includes this useful—if chilling chart from Data for Progress:

I remember when Air America was launched as an alternative to conservative talk radio like Rush Limbaugh, with hosts like Al Franken, Rachel Maddow and Mark Green. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work.

Democrats love to focus on the media because they’re media mavens—talented, creative, liberals who believe what they do in Hollywood and New York is just as important as what goes on in Washington, and they’re deeply offended that everyone else doesn’t understand that.

The bigger picture is why voting has become what the late Steve Jobs said about his invention of Apple TV—a “hobby product.” With control of the House in 2026 within reach for Democrats by turning out their traditional base and riding what’s increasingly looking like a coming blue wave, we may not need to solve that problem today—but we will tomorrow.