I often quote

and his recent Substack at is worth reading in full. He cites some of the same data I’ve also written about to explain why “the GOP Congress passed the least popular piece of major legislation since the advent of modern polling nearly a century ago.”So once again, why would these people—who love power—pass a bill that vastly increases their chances of losing it?

The answer is simple, and the same one that explains how we ended up electing a convicted criminal who sparked a violent insurrection and whose knowledge of how government works would be insufficient to pass the citizenship test:

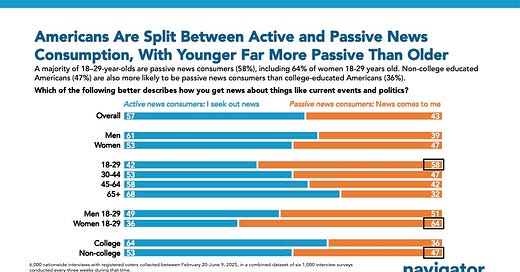

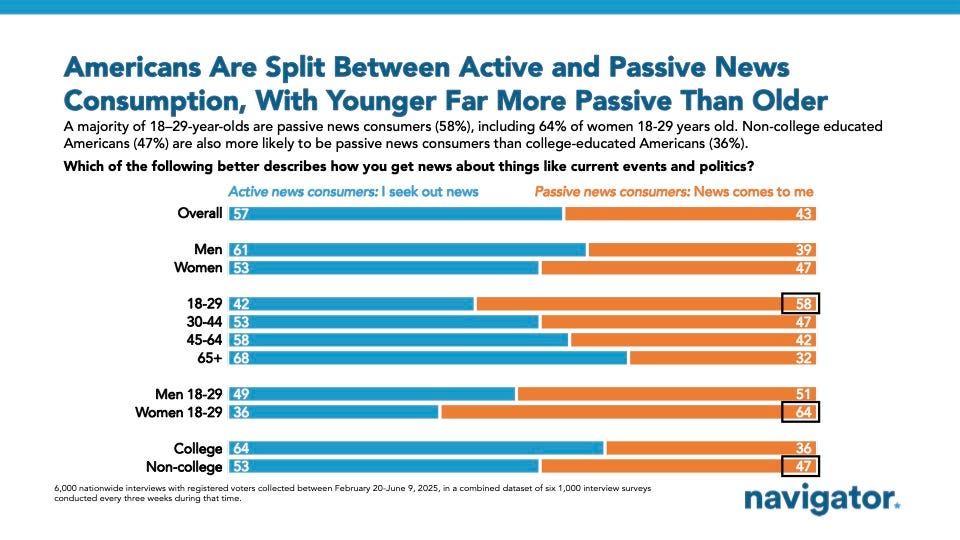

Our media ecosystem is fundamentally broken. It has become nearly impossible for all but the most engaged news consumers to follow what is happening in politics. The biggest chasm in politics is no longer between the Right and the Left—it’s between those who follow the news religiously and those who passively or actively avoid politics. Democrats do quite well with the former and struggle mightily with the latter.

Trump benefits from a media environment powered by algorithms—where facts are fluid, context is impossible, anyone can be an “expert,” and the least credible voices are elevated above everyone else.

Dan Pfeiffer quotes the analysis from Data for Progress that I included in that column titled, “When You Don't Care Enough To Vote The Very Best."

This chart shows that “Harris won with voters who pay serious attention to political news. Among those who don’t, her support collapsed, giving Trump a clear advantage.”

Navigator Research calls the people we need to reach “passive news consumers.”

Citing that analysis, Dan Pfeiffer writes:

The people we need to reach to win back the House and Senate are the 38% of midterm voters who don’t actively seek out the news. These folks have very different media diets than you and I. Social media is where most of them get their news.

Only 17% consider CNN to be a major source of news. Only 8% say that about national newspapers. I love complaining about the New York Times’s headlines as much as the next person, but this data makes clear that the voters we need to persuade are paying no attention to the Times. The big battles over their headlines and story choices are mostly an insular conversation among people whose vote was never in doubt.

This is why I’m still not watching Joe and Mika, or listening to my morning Roundtable on my local NPR station (which is too bad—the host, Joe Donahue is the best interviewer I’ve come across since that other Donahue). Those insular conversations aren’t as much fun as they used to be.

I agree with every noun and syllable in what Dan Pfeiffer wrote, but die-hard New York Times enthusiast that I am, I feel obliged to observe that what the Times (and other “legacy media”) covers gives social media and progressive media something to riff on.

If we didn’t have those independent, carefully edited and keenly reported news outlets, we’d have to make up our facts, like they do on Fox News.

With apologies to (the OG) Robert Kennedy,

Each time a New York Times story makes news, it sends forth a tiny ripple of messaging, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current in social media which can sweep down the mightiest walls of resistance to voting.

Or can it?

My question for

, and some of the other folks I like to quote here, is how do we know that reaching people, particularly young people, on social media will get them to become a voting bloc powerful enough to counter not only the new MAGA coalition (I won’t call it a “majority”—and neither will ) but also what I wrote about earlier:It’s the 42 percent solution—if you’re trying to “solve” how to keep political power in the hands of billionaires, special interests and oligarchs.

42 percent of young people ages 18-29 turned out to vote in 2024, according to data from the non-partisan research center CIRCLE, down from 50% in 2020.

But voters aged 50 or older were 52 percent of the electorate.

They’re the ones electing officials who won’t vote for gun safety, health care, voting rights, the environment, gender equality and racial justice, and all the other issues that younger voters care about

Not coincidentally, those voters are also the ones still reading newspapers and watching CNN.

As I wrote in this column, it is possible to win elections—even pull off astonishing victories—by using social media and progressive outlets to reach previously untapped blocs of young voters.

But what if your name isn’t Zohran Mamdani?

How do we get young voters to turn out in swing districts, particularly ones now held by Republicans, where the Democratic nominee might not be so cool?

I think it will start, as I’ve said before, with winning back the House, installing Hakeem Jeffries as Speaker and Jamie Raskin as Judiciary Committee Chair and showing voters what Democrats stand for.

As Dan Pfeiffer points out,

The 2024 election was decided by two groups: people who voted for Biden in 2020 and Trump in 2024, and first-time voters—groups Democrats lost in 2024 for the first time in a very long time.

A recent study from Pew Research of voter turnout in 2024 found that among young voters who were eligible to vote in both elections (those ages 22 to 34 in 2024), there was a 3 percentage point difference in the rate at which Biden’s 2020 voters turned out in 2024 (77%) compared with Trump’s voters (80%).

The Pew study found that 15 percent of Biden’s 2020 voters didn’t vote at all in 2024, and that Trump succeeded in turning out a new electorate built on “low-propensity" voters.

As I’ve said here before, the only thing that matters now is winning back the House. But we still need to address what I’ve called the “dog food problem,” quoting the former Virginia Congressman who said if the Republican Party were a brand of dog food, “they'd take us off the shelf and put us in a landfill."

Now it’s both parties, along with any belief that voting or politics can make a difference in people’s lives, or should be taken any more seriously than professional wrestling.

And our elections are being determined by those “low-propensity” voters, people who don’t have dogs, but are persuaded to buy dog food anyway1.

How do we get enough of those progressive non- dog-owners voters to vote in the midterms?

It’s not all about TikTok, is it?

Anyone notice I’ve used that language before? Didn’t think so.